May 2, 2023 | by Wong Fleming Updated May 18, 2023.

This May, Wong Fleming takes the opportunity to recognize and celebrate Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders for their contributions throughout the legal industry.

Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month is celebrated in May in the United States. It is a time to recognize and celebrate the contributions, achievements, and history of AAPIs in the United States. AAPI Month was first recognized by Congress in 1978 and was expanded to a month-long celebration in 1992. The AAPI category encompasses a wide range of individuals with various ethnic and national backgrounds, such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, Vietnamese, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Nepalese, Sri Lankan, Cambodian, Laotian, Thai, Indonesian, Malaysian, Native Hawaiian, and many more. As of 2019 there were more than 19.5 million Asian Americans in the U.S. and they are the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in the country according to Pew Research Center analysis.

Throughout history, AAPI lawyers have played a critical role in shaping the law and fighting for justice. From the civil rights hero Wong Kim Ark, who successfully argued for his right to citizenship in the landmark Supreme Court case of 1898, to contemporary legal professionals, AAPI individuals have made significant strides in various areas of law, including civil rights, immigration, and intellectual property. Their dedication and hard work have paved the way for future generations of AAPI lawyers and continue to inspire progress in the legal field.

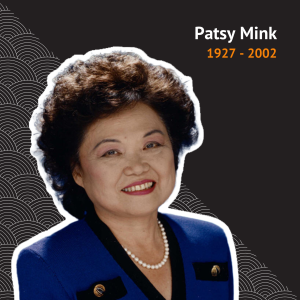

Patsy Mink (1927-2002)

Patsy Mink was a third-generation Japanese-American who grew up in Hawaii and graduated from the University of Chicago Law School in 1948. She faced discrimination due to her marital status and being a mother when she was denied the right to take the bar exam in Hawaii. Despite this obstacle, she challenged the law and eventually passed the bar. However, her struggle was not over, as she faced further rejection when seeking employment because of her interracial marriage. In response, she opened her own law practice in 1953. She founded the Oahu Young Democrats in 1954 and became the first Japanese-American woman to practice law in Hawaii. Patsy Mink’s work in challenging discriminatory laws led to her being elected as the first woman of color and first Asian American woman to hold a seat in Congress in 1964. She authored bills such as Title IX, the Early Childhood Education Act, and the Women’s Educational Equity Act. Mink was also the first Asian-American woman to run for U.S. President. She served six terms in the House of Representatives and died in Honolulu in 2002. The Title IX law was renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act after her death.

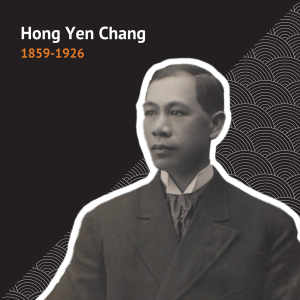

Hong Yen Chang (1859-1926)

We also recognize Hong Yen Chang who was reportedly the first Chinese immigrant to earn a law degree in the United States and the first to be licensed to practice law in any state. Chang was born in Guangdong, China in 1859 and was among the 120 students chosen to study in the United States under the Chinese Educational Mission in 1872, a program designed to teach Chinese youth about Western culture. Mr. Chang attended Yale College (currently known as Yale University) until the Chinese government terminated the Educational Mission program in 1881, which compelled Mr. Chang to halt his studies at Yale and depart back to China. Mr. Chang nevertheless returned to the U.S. and enrolled at Columbia Law School. Chang was highly recommended for bar admission after graduating with honors from Columbia Law School in 1886, but he was refused due to the Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred him from obtaining U.S. citizenship. In 1887, the New York Court of Common Pleas issued him a naturalization certificate, and the state legislature enacted a law permitting him to reapply to the bar. Upon his admission, Mr. Chang became the only regularly admitted Chinese lawyer in the United States. When he relocated to California, the state Supreme Court denied him admission to the Bar, stating that the naturalization certificate issued by New York was invalid. Chang couldn’t practice law in California but had a successful career in banking and diplomacy. In 2015, he was posthumously granted admission to the California State Bar after several petitions.

Chang’s legacy lives on as a symbol of perseverance and determination in the face of discrimination, and his case helped pave the way for greater inclusivity in the legal profession.

Cecilia Moy Yep (“Godmother” of Chinatown)

Lastly, we also recognize Cecilia Moy Yep, a remarkable figure in Philadelphia’s Chinatown, who has dedicated her life to preserving the cultural heritage of her community and advocating for its well-being. Born in North Philadelphia to a Cantonese father and German mother, Yep moved to Chinatown at around 8 years old, where her family stood out as one of the only Catholic families in the predominantly Cantonese community. The Chinatown of her childhood was a vibrant but challenging place, teeming with bars, prostitution, and industrial zones.

However, in 1941, a pivotal moment for the community occurred after the Holy Redeemer Church and School was built at 915 Vine Street. Recognizing the need for education and a sense of belonging, the school accommodated non-English speaking children and welcomed students from non-CatholicChinese families as well. This inclusive environment became a focal point for many lives in Chinatown, including Cecilia Moy Yep, who would later play a pivotal role in defending its existence.

In 1966, Yep entered the public sphere when the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation proposed expanding the Vine Street Expressway. Realizing the devastating impact this would have on the community, Yep emerged as a leader and formed a committee to oppose the project. If implemented, the project would fragment the community, demolish the beloved Holy Redeemer Church and School and displace many residents including Yep, then a widow of three small children. Yep stood her ground at her home on 832 Race Street, even as bulldozers moved forward and her neighbors abandoned their homes. Yep referred to her steadfast determination as “The Alamo of Chinatown.”

Yep and her supporters’ efforts eventually bore fruit when the city and Penn DOT ultimately redesigned the Vine Street Expressway project to spare Holy Redeemer, installed noise-reducing walls along the expressway, and abandoned plans for a 9th Street ramp. The victory marked a turning point and solidified Cecilia Moy Yep’s reputation as a tenacious defender of Chinatown.

In 1969, the committee formed to oppose the Vine Street Expressway was incorporated as the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC), a grassroots nonprofit organization committed to promoting Chinatown as a thriving residential and commercial community. In 1974, Yep assumed the role of executive director, leading the PCDC’s mission with dedication and foresight.

Yep and the PCDC continued their battle against various projects encroaching upon Chinatown, including Market Street East, Gallery I and II, a new commuter terminal, and the Convention Center. They successfully lessened the negative impact of six public projects, stopped the construction of a new bus terminal and a federal prison conversion, but residents still faced challenges like displacement, limited space, and rising real estate prices.

However, Yep and the PCDC were not deterred. To counter these challenges, they spearheaded the construction of five housing developments within Chinatown: Mei Wah Yuen (Beautiful Chinese Homes), Wing Wah Yuen (Dynasty Court), Gim San Plaza (Gold Mountain), On Lok House (Peace and Harmony), and Hing Wah Yuen (Prosperous Chinese Garden). These developments comprised a total of 216 residential units and 22 commercial units, providing affordable housing options while preserving the neighborhood’s cultural character.

Yep resigned as executive director of PCDC in 2000, but she remains very active in making sure PCDC fulfills its mission to Chinatown. Her legacy in Chinatown continues to grow and influence the community today and future generations. In 1999, she initiated the passage of a bill that established Chinatown as a Special Zoning District, rezoning 44 acres of underutilized land located north of Vine Street and across from Chinatown, creating opportunities for the community to expand. Furthermore, in November 1982, Yep helped represent Chinatown in a trade mission to China that resulted in an agreement with Philadelphia’s Sister-City, Tianjin, to provide materials for the remarkable ChinatownFriendship Gate. The Gate was completed in 1984 and now stands as the iconic entrance at 10th and Arch streets.